I’m hoping you all already installed python and sublime text (or an IDE of your choice) according to your operating system since I won’t be wasting time on that. Actually I got no way to waste time on that since I got no windows and Linux comes with python pre-installed. Check this if you haven’t installed python and this for installing sublime text on windows. For Ubuntu derivatives just do:

1

sudo snap install sublime-text --classic

Opening the shell

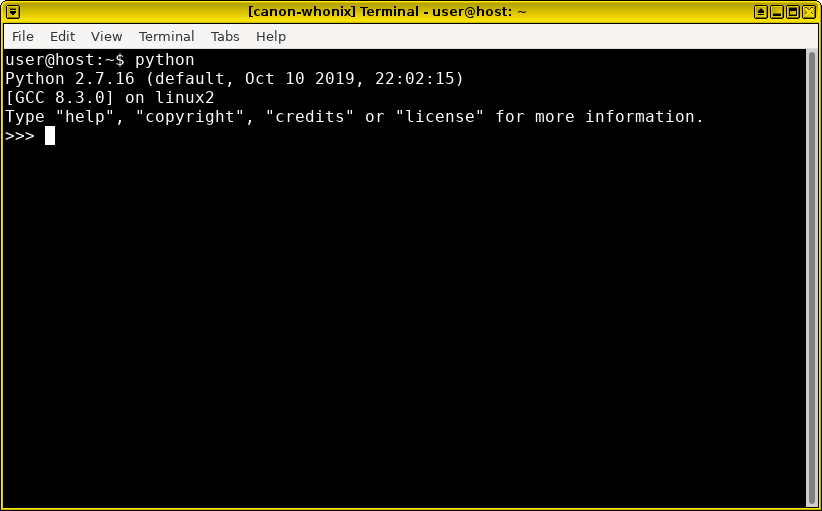

Some of the stuff we’ll do today do not need to be created as files to work and can be worked off just the shell. The shell is the place where you can enter commands without making files and they’ll be run by python. To enter the python shell all of you on windows can just open the IDLE application that is installed on your computer. For Linux you can just run python3 in your terminal. You can exit this shell by running exit() on Linux. I’m not sure if that works for windows but you can always just close the window.

Difference between compiled and interpreted languages

I want to first talk about how this all works in general before we start to code anything. The major difference between programming languages is whether the code is compiled beforehand or simultaneously while running. Some coding languages like C++ and C# need to translate (compile) the code beforehand and create a separate file (in assembly language) that the interpreter (the program that will run your your code) can understand. These languages are called compiled languages. On the other hand, languages like python compile and interpret simultaneously. These languages are called interpreted languages. The downside of using the python way is that your code won’t be as theoretically efficient. But this difference in efficiency fades when we realize that humans can’t even write code that is efficient enough to make a difference. So for you it won’t make a difference for a long time. And when it does start to make a difference, there are ways to compile the python code you have before running using modules like Cython. The upside of interpreted languages is that the syntax is easier to understand.

For compiled languages:

For interpreted languages:

Hello World

Almost all python classes–actually all programming classes–start with printing “Hello world” to the screen so I want also to get that out of the way.

1

2

>>> print('Hello World!')

Hello World!

print() here is the function we use to print objects to the screen. Just like math functions, functions in python usually take parameters and return an output. But more on functions later!

You can also enter multiple parameters to a single print() function just like you can give multiple parameters to a math function (e.g. \(f(x,y)\) ).

1

2

>>> print('Hello World!', 'and ikbal')

Hello World! and ikbal

As you can see, when you separate two objects by a comma in the print() function, print() will automatically add a space between them.

Another thing to note about the print() function is that, on it’s own it will print a \n character. \n is just a newline.

1

2

>>> print()

Although please note that the print function is run by default in your shell. That’s what a shell does. This won’t be the case for your “real” applications so I will continue using print() to get you accustomed to it.

1

2

>>> 'Hello World!'

Hello World!

What objects?

I like to make this course more focused on the object-oriented part of python because although it may sound hard now, this will ease a lot of stuff. You might have found it odd that I’ve said python prints objects to the screen in the ‘Hello World!’ example. But it is in fact true. Every single ‘thing’ in python is an object. That print() function? Object. That \n character? Object. Hello world? Object. Now to avoid confusion and more so to make this language actually work, we need some objects to be different than others and this brings us to object types.

Object types

There are some main object types that you need to keep in your mind if you want to be able to make sense of error messages. But how do we get an objects type? Well there’s an function that does that for us. And it’s surprisingly called type(). So let’s figure out the type of some objects we can think of in the shell:

1

2

>>> type(5)

<class 'int'>

The 'int' part here denotes the type of the object. In this case it is an integer. Integers are whole numbers like 3, 4, 5 or 345.

1

2

>>> type(5.2)

<class 'float'>

Here the type of 5.2 is float. To be honest the difference between floats and integers now don’t matter. It used to be that you needed type conversions and there were some stupid conflicts in python2 but now they’re obsolete. Anyway, float stands for ‘floating point numbers.’ Any number that you write with a ‘decimal point’ has this type. For example 9.2E8 is also a float.

1

2

>>> type({0, 1, 2, 3})

<class 'set'>

Just like in math, we have sets here too. But unlike math we can put any type of object we want in them, not just integers and floats. They’re unordered clumps of objects but an important feature you need to keep in mind is that a single object only exists once in a set, that is, there are no duplicate objects.

1

2

>>> print({'kuzey','kuzey'})

{'kuzey'}

Moving on.

1

2

>>> type([0, 1, 2, 3])

<class 'list'>

So anything you put between square braces is a list. A list is an ordered set. That’s it. We’ll get to how to use each of these later.

1

2

>>> type((0, 1, 3))

<class 'tuple'>

Tuples are just like lists but the difference is that you can’t change them. Again, we’ll get to these later.

1

2

3

4

>>> type(True)

<class 'bool'>

>>> type(False)

<class 'bool'>

Another type that we have is boolean. This is a simple True or False statement. We’ll make use of this when we get to how to write logical expressions.

1

2

>>> type('')

<class 'str'>

The last type, at least for now is string. Strings are anything you put inside ‘ ‘s. You can also use “ “s but you should be consistent with what you use. Most people think about writing when thinking about strings. Yes that is true, but only to an extend. I wouldn’t like to confuse you but '3' is also a string.

1

2

>>> type('3')

<class 'str'>

So just keep in mind that anything between quotes is a string although strings have text inside them most of the time, they can have any character you want. (Except the escape character on it’s own, i.e. \)

This brings us to another thing you should note related to print(). The escape character: \. Backwards slash–unless it’s used before certain characters like n and t–will disable the next character. What do I mean by this? Let’s see:

1

2

3

4

5

>>> print('It isn't so')

File "<stdin>", line 1

print('It isn't so')

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Even from the highlighting you can see that there’s a problem. What happened here was python took 'It isn' as a string and left out t so. So in cases like this you use \ before ' to deactivate it. Or use " instead of '

1

2

3

4

>>> print('It isn\'t so')

It isn't so

>>> print("It isn't so")

It isn't so

Type conversions

The last thing you should know about types is that you can convert them to each other. You can use the commands int(), str(), list(), set() for example, to do this. If we want to see it in action:

1

2

>>> type(int('5'))

<class 'int'>

1

2

>>> type(int('5'))

<class 'int'>

1

2

3

4

>>> list(5)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'int' object is not iterable

So keep in mind that you can’t turn every type to every other type. We’ll see why this is in later lessons since that requires us to learn a lot deeper about how lists work.

But what happens if we don’t include the quotes in strings? Let’s see.

1

2

3

4

>>> ikbal

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'ikbal' is not defined

So here we face a NameError. And it clearly tells us that python doesn’t know what this is. But not all hope is lost. We can define what this text is.

1

2

3

>>> ikbal = "awesome"

>>> print(ikbal)

awesome

So by defining this meaningless text, we made it a variable. Our ikbal variable has the value "awesome". And we did it by using the = operator. You should note that there are reserved words that you can’t use for variables because they already have a meaning. Altough, when you’re using sublime, these words will be highlighted so you won’t have any trouble. These words are: and, as, assert, break, class, continue, def, del, elif, else, except, False, finally, for, from, global, if, import, in, is, lambda, nonlocal, None, not, or, pass, raise, return, True, try, while, with, and, yield.

Here’s a table of some data types and examples:

| What is it? | Name | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Text (Anything inside ‘’ actually) | string | ‘ikbal’, ‘12345’, ‘print()’ |

| Whole numbers | integer | 3, 4, 5, 345 |

| Decimal numbers | float | 5.2, 6.8, 9.2E6 |

| True or False | boolean | True, False |

| Sets | set | {‘ikbal’, ‘kuzey’}, {1, 5, ‘ikbal’} |

| Lists | list | [0, 1, 3, 4], [‘ikbal’, ‘kuzey’, ‘ikbal’] |

Operators

All these brings us to operators. Yes, I know, it’s not as exciting to learn about data types and these basic stuff, but it’ll be over soon. Operators are just like in math. They operate. I don’t think high level explanations are very memorable so let’s see some operators. Operators are type-specific, meaning that either they don’t work for different types or that they work differently for different types. Don’t try to memorize these. Try writing code that uses these operators. That’ll make them stick more easily.

Integer and float operators

Addition

1

2

>>> 3+5

8

Subtraction

1

2

>>> 3-5

-2

Multiplication

1

2

>>> 3*5

15

Integer division

1

2

>>> 3//5

0

Division

1

2

>>> 3/5

0.6

Remainder or mod

1

2

>>> 3%5

3

Raise to the power

1

2

>>> 3**5

243

Note: The same “order of operations” rules apply here too.

String operators

Appension or glueing strings together

1

2

>>> 'ik' + 'bal'

'ikbal'

Repetition

1

2

>>> 3*'ikbal '

'ikbalikbalikbal'

List operators

List comprehension is a wide subject and there are lots you can do with lists. They are probably the most important and useful type if we don’t count booleans. But I’m not going to be focusing too much on that for this section since it won’t be memorable. We’ll have a section going in depth with lists soon. Some basic operations you should keep in mind are

Addition

1

2

>>> [0,1] + [2]

[0, 1, 2]

Multiplication

1

2

>>> [0,1]*5

[0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1]

Indexing

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

>>> [0, 1, 2, 3][0]

0

>>> [0, 1, 2, 3][1]

1

>>> [0, 1, 2, 3][2]

2

>>> [0, 1, 2, 3][3]

3

Assignment operators

= You know this one.

+=

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> a = 5

>>> print(a)

5

>>> a += 5

>>> print(a)

10

*= and -= You should be able to guess.

Membership operators

in

1

2

>>> 'e' in 'election'

True

Identity operators

is

1

2

3

>>> a=3

>>> a is 3

True

Comparison operators

==. Same with is. It checks whether objects on the ends are the same.

1

2

3

>>> a=3

>>> a == 3

True

!= (Not equal)

1

2

>>> 'ikbal' != 'ugly'

True

There’s also >, <, >=, <= but I’m sure you can guess what they do.

Logical Operators

and, or

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

>>> True and False

False

>>> True and True

True

>>> False and False

False

>>> True or False

True

>>> False or False

False

Expressions

To be honest, all we were doing in the last section was checking the values of expressions. When you use objects with operators, you get expressions. For example a = 5 is an expression just like a is 5. Some of these expressions are logical arguments. You may have noticed that in a big part of the operators we just saw, the shell returned either True or False. These expressions which return True or False are called logical statements just like in math. This brings us to branching.

Branching

Branching despite it’s impressive name only means checking for a condition and running (or not running) code based on that condition. The basic statements for branching is if, elif and else. Remember the comparison operators? This is where we’ll use them.

With branching, it’ll be harder to use the shell so we’ll now move on to using Sublime Text for the first time.

Go ahead and press Ctrl + s, pick a folder and name your file. Make sure your file has a .py extension. Alright, now we’re ready to write some code. For the first example, let’s test how if works.

1

2

if True:

print("It's alive!")

Do not forget to add a column after the if statement! This is just how the syntax of python is and there’s no way to get around it. Python is strongly dynamically typed, meaning that if you made a mistake in the way you’re writing something, it will get angry pretty quick. Notice how we also put 4 spaces (or 1 tab) before the second line. This tells python that the print statement will only run if the if statement runs.

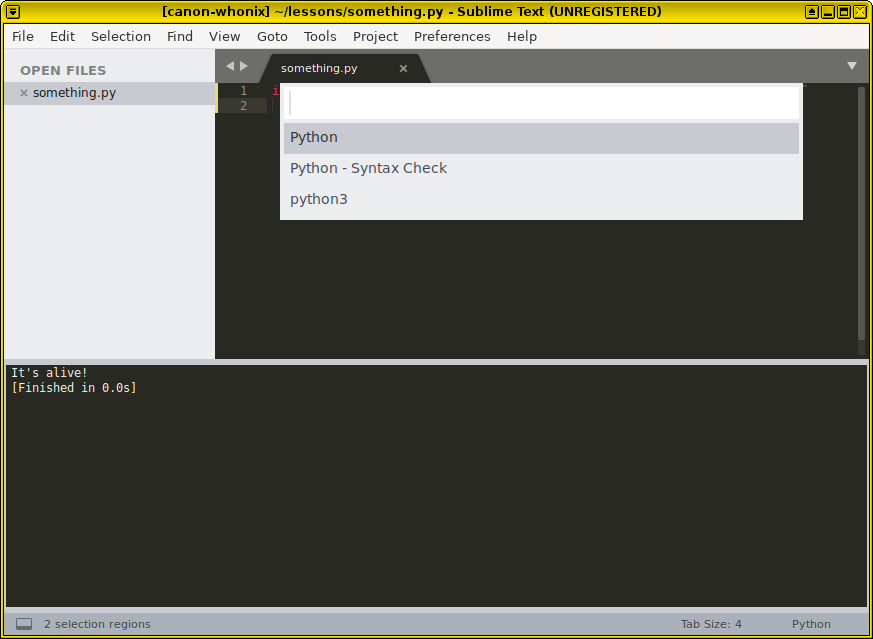

To run a file with Sublime Text, press Ctrl + B.

Then click the Python option.

If you’re on Linux, by default Sublime Text will try to use python2. To fix this see Fixing Sublime for Linux. Also, note that this won’t work for files that prompt the user to input something but we’ll get to that later. So now, on the window below, you should be seeing:

1

2

It's alive!

[Finished in 0.0s]

It is also possible to run this from the terminal on Linux and from cmd on Windows. You simply need to cd to the location of the file and do python3 filename.py

Enough Sublime Text, let’s get back to how branching works.

What happened?

- The interpreter, when parsing the file comes to the if statement and stops.

- The interpreter checks whether what comes after it is True. So in this case, the interpreter checks whether

Trueis True. - If the statement is True, then python runs the indented part under the

ifstatement.

Let’s try some other examples:

1

2

3

4

ikbal = 'pretty'

if ikbal == 'pretty':

print("Ikbal is pretty!")

Beware how we use the comparison operator in the if statement! The output is:

1

2

Ikbal is pretty!

[Finished in 0.0s]

Sure enough. We defined the variable ikbal to have the value 'pretty' so the if statement ran. Let’s try to build a bit on this example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

ikbal = 'pretty'

if ikbal == 'pretty':

print('Ikbal is pretty!')

elif ikbal != 'ok':

print('Ikbal is not ok.')

elif means else-if. It may run if the if statement doesn’t run.

And the output is still:

1

2

Ikbal is pretty!

[Finished in 0.0s]

What happened?

- The interpreter checked the

ifstatement. - The

ifstatement ran, so the interpreter didn’t check theelifstatement even though it wasTrue.

That’s fair. Let’s make this a bit more complicated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ikbal = 'ugly'

if ikbal == 'pretty':

print('Ikbal is pretty!')

elif ikbal != 'ok':

print('Ikbal is ok.')

else:

print('Nope.')

Notice how we changed ikbal’s value to 'ugly'? This time the output is:

1

2

Ikbal is ok.

[Finished in 0.0s]

What happened?

- The interpreter checked the first if statement. It was

Falsebecauseikbal!='pretty'. - The interpreter checked the

elifstatement and it wasTruebecauseikbal!='ok'. - The interpreter didn’t run the

elsestatement.

So from this we can deduce:

elseonly runs when none of theiforelifstatements ran.

Let’s test our deduction. We’ll set ikbal to be 'ok'. Before running try to guess what’ll happen on your own. It’s always a good exercise to guess before you run your code so you may have a clue where you go wrong.

Our guess

- The interpreter will check

ifikbal=='pretty'and it will returnFalsebecause it isn’t. - The interpreter will check

elifikbal!='ok'and it will also returnFalsebecauseikbalis'ok'and the statement returnsTrueonly whenikbalisn’t'ok'. - The

elsestatement will run because nothing else did.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ikbal = 'ok'

if ikbal == 'pretty':

print('Ikbal is pretty!')

elif ikbal != 'ok':

print('Ikbal is ok.')

else:

print('Nope.')

And the result is:

1

2

Nope.

[Finished in 0.0s]

So our guess was correct.

The last thing about branching that you need to know is nested branching. As it’s name it’s about nesting different branches.

Nested branching

Open a new file and name it whatever you want (It should end with .py). This one is so simple that you don’t even need an example for it but here goes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

num = 5

if num%1 == 0:

print("This number is divisible by 1")

if num%2 == 0:

print('This number is also divisible by 2')

Remember the % operator? Here’s we’re making use of it. As you remember x%y gives us the remainder from dividing x by y. And our output is:

1

2

This number is divisible by 1

[Finished in 0.0s]

What happened?

- The interpreter checked

ifthe remainder from dividingnumby 1 was 0. (So it checked whethernumwas divisible by 1) And 5 is divisible by 1 so it ran the indented code. - It ran the

print()function - The interpreter faced another

ifstatement and checked whethernumwas divisible by 2 and 5 isn’t divisible by two so it didn’t run the double-indented part of the code.

Note that if the first if statement didn’t run, the interpreter wouldn’t check the indented if statement. The indented code only runs if the if statement runs.

This brings us to the end of branching and to the last subject I want to talk about in this lesson.

Functions

You already saw one of these: the print() function. You’ll come across more and more functions as you delve deeper. Don’t make an effort to memorize them all at once, they won’t stick. For this reason, this section doesn’t focus on different functions you can use for different things but rather how to make your own functions.

Again, functions in python work just like the functions in math. They take a variable and return a value. Accordingly we use the def function to define functions. Think about a mathematical function we can write in python. How about \(f(x)=x^2\)? Let’s see how it’s done:

1

2

def f(x):

return x**2

Don’t forget the : after your function! The syntax here is trivial to get used to. We write def followed by the name of our function and the imaginary input our function takes in parenthesis. Like we did with if statements we add a column (:) after the def statement and indent the following lines. This tells python that the indented part belongs to this function. return, also accordingly, is the command we use to define what this function will return to us. This is basically saying f takes x and gives us x**2. (Check what ** does.)

All well and good. But as you see, obviously, when we run out code, we get nothing. That’s because we didn’t actually run the function, we only defined it. To run the function we add f(2) to the end of the file (Don’t indent it since we are not defining the function anymore). So it becomes

1

2

3

def f(x):

return x**2

f(2)

But as you see, we still get nothing when we run this command. And that is because we didn’t tell python to print the output to the screen. We merely ran the command. Let’s print it and see

1

2

3

def f(x):

return x**2

print(f(2))

Sure enough, now we’re getting what we expect.

Let’s see another example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def ikbalchecker(x):

if x == 'pretty':

return 'ikbal'

else:

return 'not ikbal'

print(ikbalchecker('ugly'))

As you can see we can use if statements inside functions. What this function does is to check whether x is 'pretty' and if it is it returns 'ikbal'. As you can also see, our functions don’t have to be about numbers. When we run it we get:

1

2

not ikbal

[Finished in 0.0s]

As expected. And now for the last example:

1

2

3

4

def yanker():

print('yank')

print(yanker())

So you see here that we don’t even have to give anything to our function to do something and we don’t even need the function to return something. Let’s run it and see what happens:

1

2

3

yank

None

[Finished in 0.0s]

Oh wait. Why is there None there? The problem here is with how we used our function not how we defined it. You see, we defined the function to print something and then we printed our function. We know what print does. It runs what we give it, and then it prints the value of it to the screen. Because we didn’t make a our function return anything so it by default has the value None. And print() printed what we told it to print. What were we supposed to do? This:

1

2

3

4

def yanker():

print('yank')

yanker()

And now it returns

1

2

yank

[Finished in 0.0s]

So in essence, if you tell a function to print, don’t print the function. If you tell it to return something, print it.

Homework

Fixing Sublime for Linux

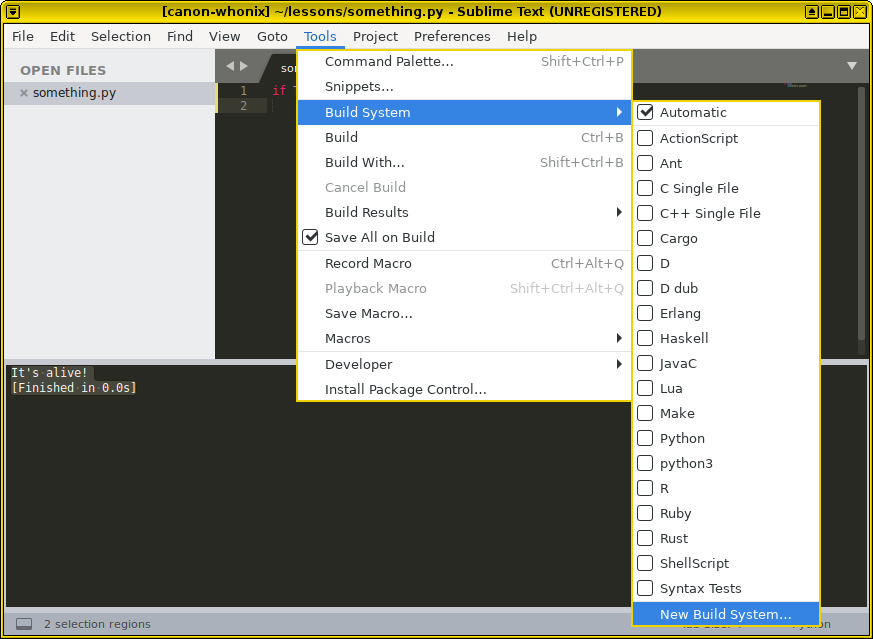

Go into

Tools > Build System > New Build System...

Delete what is already in the file.

Paste the following code in:

1 2 3 4 5

{ "cmd": ["/usr/bin/python3", "-u", "$file"], "file_regex": "^ ]*File \"(...*?)\", line ([0-9]*)", "selector": "source.python" }

- Save the file with

Ctrl + s. Don’t change the location, just name itpython3.sublime-build. - Go into

Tools > Build Systemand select ‘python3.’