Input

Here we’ll make use of the input() function (gasps).

Example 1

1

2

3

>>> input()

boo

'boo'

Here you might notice that input() acted like the echo command in bash. To be honest, this is all there is to it. When you use input(), the interpreter will wait for you to enter an input and then store that input in temporary memory.

Example 2

In a program we can capture this input and store it in a variable

1

2

our_input = input()

print(our_input)

Like I’ve mentioned before, you can’t run this in Sublime, so we’ll launch a terminal and run it there.

1

2

3

$ python3 input.py

hello

hello

Sure enough, it works. And that’s all there is to it. The last thing to keep in mind can be, no matter what you enter, input() will give you a string (So the users can’t input arbitrary commands and take over your program). So if you want to work with integers you need to first convert your input to an integer.

1

2

3

>>> type(input())

123

<class 'str'>

1

2

3

>>> type(int(input()))

123

<class 'int'>

Default arguments

This section is very simple. It is basically about giving function arguments a default value. (remember how print() had a default argument \n?)

Example 1

Let’s make a function that will invert a boolean it takes. For example if we give it True it’ll give us False. And let’s make it use True by default.

1

2

def invert(arg = True):

return not arg

and that’s all there is to it! If you want a default for an argument, just do arg = <your desired default> where you define your arguments.

Scoping

The point of scoping is, to each his own. What do I mean by that? I mean that if you define a variable inside a function, that variable is local not global meaning, it is only defined inside that function.

Example 1

Let’s make a function and define a variable inside it. Afterwards, we’ll try printing our variable.

1

2

3

4

5

def definevar():

x = 4

print("Value of x inside the fn", x)

definevar()

print("Value of x outside the fn", x)

Output:

1

2

3

4

5

Value of x inside the fn 4

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/user/lessons/scoping.py", line 5, in <module>

print("Value of x outside the fn", x)

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

As you see, the print statement inside our function ran just fine, but the one on the outside didn’t because x was only defined inside the function.

Example 2

Let’s try analyzing the code below

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

def f(x):

def g():

x = 'abc'

print("x =", x)

def h():

z = x

print("z =", z)

x = x+1

print("x =", x)

h()

g()

print("x =", x)

return g

x = 3

z = f(x)

print("x =", x)

print("z =", z)

z()

Output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x = 4

z = 4

x = abc

x = 4

x = 3

z = <function f.<locals>.g at 0x7f34648cdbf8>

x = abc

Oh wow. Now what happened here? Let’s trace it back

line 15

x = 3line 17

z = f(x)line 8

x = x+1line 9

print("x =", x)line 10

h()line 6

z = xline 7

print("z =", z)This will print a local variable and not the one in 2.

line 11

g()- line 3

x = 'abc' - line 4

print("x =", x)

- line 3

line 12

print("x =", x)line 13

return gNotice how we return the

gfunction itself. Sof()’s value is a function itself. This means when we doz = f()thenz == g. This is why we gotz = <function f.<locals>.g at 0x7f34648cdbf8>in our output.

line 19

print("x =", x)line 20

print("z =", z)line 21

z()Since

z == gthis is basicallyg()

But how do we define a global variable inside a function? Is all hope lost? Simple:

1

2

3

4

5

def f():

global x

x = 5

f()

print(x)

Output:

1

5

globalallows us to make our variables global. (shocking!)

Recursion

Recursion is calling a function inside that function. What do I mean?

Example 1

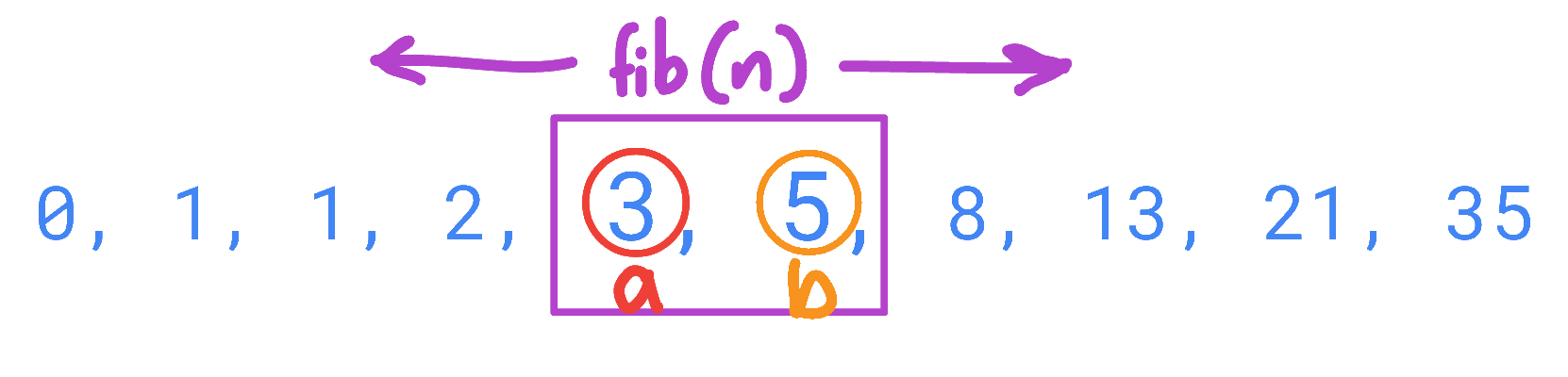

Consider the Fibonacci function

1

2

3

4

5

def fib(n):

a,b = 0,1

for i in range(n):

a,b = b, a+b

return a

To understand this function better, let’s take a look at the values a and b have for i in range(n)

| Step | a | b |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 5 |

| 5 | 5 | 8 |

| 6 | 8 | 13 |

| 7 | 13 | 21 |

| 8 | 21 | 35 |

So we’re just slowly shifting our pairs through the Fibonacci set here. I like to think of it like we’re sliding a magnifier through the Fibonacci set.

How might we write this with recursion? Simple. Actually it’s simpler than the one without recursion. Let’s remember what the Fibonacci function actually meant.

\( F(N) = F(N-1)+F(N-2) \) where \( F(0)=1 \) and \( F(1)=1 \)

This seems like the exact recipe for a recursive function, doesn’t it? Translating math into pseudo-code (code that doesn’t run) we’d get:

` fib(n) returns fib(n-1) + fib(n-2) where fib(0) returns 1 and fib(1) returns 1`

So first we’ll check if n is 0 or 1 and return 1 if that’s the case. If not, we’ll return fib(n-1)+fib(n-2).

1

2

3

4

5

def fib(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-1)+fib(n-2)

Done.

Example 2

A palindrome is a phrase whose characters are read the same from the left or the right. For example: “Madam, I’m Adam.”

In this example we’ll try to make a function that tests whether a string is a palindrome. This is also a nice opportunity for me to introduce you to the divide and conquer paradigm. Divide and conquer as it’s name is about breaking down a problem into smaller problems that are easier to handle. We’ll make a parent isPalindrome(s) function with child functions, and each child function will handle a different sub-problem of our goal. Our sub-problems are:

- Remove all spaces and punctuation from the string and turn it into a single word with all lowercase characters.

- Recursively check whether the last and the first character in our word is the same.

For the “Madam, I’m Adam.” example,

Turn our string into “madamimadam”

Check whether the first and last letters are the same

Check whether the second and second from last letters are the same.

…

We’ll first create our function and inside it, create a toChars(s) function.

1

2

def isPalindrome(s):

def toChars(s):

First we’ll redefine our string to be all lowercase.

1

s = s.lower()

To remove punctuation we’ll first make an empty string. We’ll go over our string character by character, and then, we’ll go and check if the character is a letter or a number. If that’s the case we’ll add our character to our empty string.

1

2

3

4

letters = ''

for c in s:

if c in 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz':

letters = letters + c

Finally, we can return our now sanitized string.

1

return letters

Our toChars(s) function is complete. Now, on to the isPal(s) function. This is where the magic will happen.

1

def isPal(s):

Now as you might’ve guessed we need an initial condition. To build recursive functions we need to predefine some situations so that the function has something to fall back on. In this case our initial condition is when there are no letters or only one letter left. 0 and 1 letter words are always palindromes.

1

2

if len(s) <= 1:

return True

Now if the initial condition isn’t met we’ll recursively check palindrome-ness. How might we do this? We’ll check the first and last letters; remove them from our string; and re-run our function with the shorter, new string.

1

2

3

else:

answer = s[0] == s[-1] and isPal(s[1:-1])

return answer

Here we have a logical statement. The interpreter will check the first statement, s[0] == s[-1] and then run isPal(s[1:-1]) which will check s[1:-1][0] == s[1:-1][1] and so on until len(s) is smaller than or equal to 1.

Good. Now we need to put this all together and run our functions and return the result. Think of this as composite functions.

1

return isPal(toChars(s))

And this concludes our function.

Using this example I want to introduce yet another concept: test suites. Test suites are functions that test other functions.

1

def testIsPalindrome():

We’ll keep it simple and test only two strings: dogGod (is a palindrome) and doGood (isn’t a palindrome). We’ll just print what we’re testing and a logical statement stating whether the test went fine.

1

2

3

4

5

def testIsPalindrome():

print("Try dogGod")

print(isPalindrome("dogGod") == True)

print("Try doGood")

print(isPalindrome("doGood") == False)

And finally we’ll run the tests:

1

testIsPalindrome()

The output is:

1

2

3

4

Try dogGod

True

Try doGood

True

So we’re all good!

Code in full

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

def isPalindrome(s):

def toChars(s):

s = s.lower()

letters = ''

for c in s:

if c in 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz':

letters = letters + c

return letters

def isPal(s):

if len(s) <= 1:

return True

else:

answer = s[0] == s[-1] and isPal(s[1:-1])

return answer

return isPal(toChars(s))

def testIsPalindrome():

print("Try dogGod")

print(isPalindrome("dogGod"))

print("Try doGood")

print(isPalindrome("doGood"))

testIsPalindrome()

List methods

Speaking of tying loose ends, we need to come back to lists (again, I know, but for the last time I promise)

1

>>> lis = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

Inserting: Adding an item to a list at a specific location.

1 2 3

>>> lis.insert(1, 'inserted') >>> lis [0, 'inserted', 1, 2, 3, 4]

Count: How many times an object appears in a list.

1 2

>>> lis.count(1) 1

Append: Adds an item to the end of the list.

1 2 3

>>> lis.append('appended') >>> lis [0, 'inserted', 1, 2, 3, 4, 'appended']

Extend: Adds a list to the end of another list.

1 2 3 4

>>> lis2 = ['extended1', 'extended2', 'extended3'] >>> lis.extend(lis2) >>> lis [0, 'inserted', 1, 2, 3, 4, 'appended', 'extended1', 'extended2', 'extended3']

Pop: Removes an element at an index, and also returns that element.

1 2 3 4

>>> lis.pop(0) 0 >>> lis ['inserted', 1, 2, 3, 4, 'appended', 'extended1', 'extended2']

This will remove the last element if we use it without an attribute.

1 2 3 4

>>> lis.pop() 'extended3' >>> lis [0, 'inserted', 1, 2, 3, 4, 'appended', 'extended1', 'extended2']

Reverse: Reverses a list.

1 2 3

>>> lis.reverse() >>> lis ['extended2', 'extended1', 'appended', 4, 3, 2, 1, 'inserted']

Sorting: Sorts a list.

The default sort for a list is ascending.

1 2 3 4

>>> numlist = [5, 6, 8, 10, 22, 9, 3, 1, 2] >>> numlist.sort() >>> numlist [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 22]

You can also sort lists of strings.

1 2 3 4

>>> strlist = ['a','d','c','b'] >>> strlist.sort() >>> strlist ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

Or any type of predefined object for that matter1. When sorting lists of lists, the interpreter looks at the average value of the lists.

1 2 3 4

>>> listoflist = [[0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [5, 8]] >>> listoflist.sort() >>> listoflist [[0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [5, 8]]

The one thing you cannot do is sorting a list with different types.

1 2 3 4 5

>>> lis = ['extended2', 'extended1', 'appended', 4, 3, 2, 1, 'inserted'] >>> lis.sort() Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'int' and 'str'

We could get around this by using the

keyparameter. Whatever function we give to thekeyparameter is applied to all objects and the list is only sorted afterwards.1 2 3

>>> lis.sort(key=str) >>> lis [1, 2, 3, 4, 'appended', 'extended1', 'extended2', 'inserted']

You might be confused to see the first four elements as integers not strings. Wasn’t the key supposed to be applied to all elements? Yes, it was, but that’s only temporary. The key is applied to each element and the sort is done according to the results but the original elements are the ones being sorted. So even when you define a key, only the order of the elements change, not the elements themselves.

To turn the order of sort, you can define the parameter

reverseasTrue.1 2 3

>>> lis.sort(key=str, reverse=True) >>> lis ['inserted', 'extended2', 'extended1', 'appended', 4, 3, 2, 1]

You can also use the function

sorted()which returns a sorted version of the same function.1 2 3

>>> numlist = [5, 6, 8, 10, 22, 9, 3, 1, 2] >>> sorted(numlist) [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 22]

List comprehension

Let’s try making a function that checks if an element in list l1 is also in list l2. And if it is, we’ll remove it from l1. At this point of the course, I believe it’ll be easy for you to imagine how we might do this. We just need to loop over the first list and check if the looped elements are in l2 one by one.

1

2

3

4

def removeDups(l1, l2):

for e in l1:

if e in l2:

l1.remove(e)

Let’s write a test suite and test our function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

def testDups():

l1 = [1, 2, 3, 4]

l2 = [1, 2, 5, 6]

removeDups(l1, l2)

print('l1 =', l1)

print(l1 == [3, 4])

When we run our testDups(),

1

testDups()

the output is:

1

2

l1 = [2, 3, 4]

False

Wait a second. What’s wrong? Well, the problem occurs when we try to change a list while we’re looping over it. The indexing in a for loop only happens once.

| Index | Value | The current l1 |

|---|---|---|

0 | 1 | [2, 3, 4] |

1 | 3 | [2, 3, 4] |

2 | 4 | [2, 3, 4] |

So while the numbers shift, the indices stay the same, and this causes a mismatch between elements. How can we prevent this? We’ll use list comprehension.

List comprehension offers a shorter syntax when we want to play with lists. For example to achieve what we tried with removeDups(l1, l2) we can just do:

1

2

3

4

>>> l1 = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> l2 = [1, 2, 5, 6]

>>> [element for element in l1 if element not in l2]

[3, 4]

Translating this into English: “Give me that element for each element in l1 if element isn’t in l2.”

This syntax is also useful for creating dictionaries or tuples or what have you. For example we can try creating a dictionary where keys are numbers from a list and values are True or False depending on whether the numbers are even or not.

1

2

>>> l = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> { k:not bool(k%2) for k in l }

Map and Lambda

Let’s start with map(). map() is a function that, as it’s name, maps a function to a group of objects. For example if I wanted to apply the function int() to each element in list ['1','2','3','4'] then I would simply do:

1

2

>>> map(int, ['1', '2', '3', '4'])

<map object at 0x7300d211ffd0>

As you notice, this gave us a map object instead of a list, but not to worry; we can do whatever we want with this map object as it’s an iterable. So for example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> for i in map(int, ['1', '2', '3', '4']):

... print(i)

...

1

2

3

4

Or if you don’t like not seeing what you have clearly, you can just convert your map object into a list:

1

2

>>> list(map(int, ['1', '2', '3', '4']))

[1, 2, 3, 4]

That’s it for map(). Now what does lambda have to do with all these? lambda is used to create functions. Often thought of as anonymous function creator, it actually adds no functionality and is only a shorthand form of what we regularly do to define functions. So for example think about the function \( f(x)=x^2 \). One way to define it might be

1

2

3

>>> def c(x):

... return x**2

...

But another way to define it is

1

>>> f = lambda x: x**2

So to define a function (lazily) we can just use the syntax lambda <input>:<output>. One thing to note here is that the name of the second function isn’t f. f there is just a variable we use to reference an anonymous function.

Any function you define, when you try to print it, gives you the function name:

1

2

>>> c

<function c at 0x75f4967a21e0>

But with lambda functions, there is no name to be given

1

2

>>> f

<function <lambda> at 0x75f4967a2158>

These lambda expressions become useful when we want to map a custom function but we’re too lazy to define it somewhere in our code (or we just want to keep our code simple)

1

2

3

>>> sqrtmap = map(lambda x:int(x)**2, ['1', '2', '3', '4'])

>>> list(sqrtmap)

[1, 4, 9, 16]

Homework

__lt__ and __eq__ magic methods have to be defined for an object type to be sortable. We’ll get to this later when we look at how to create our own object types. ↩